Canadian Spill Response Regime

Marine spills are the responsibility of the federal government.

The Regime

The National Oil Spill Preparedness and Response Regime provides the framework for preparedness and response for ship-source oil spills in Canadian waters south of the 60th parallel.

The regime was created in 1995 to enable industry to respond to its own oil spills. Built on the polluter-pays principle, the regime is based on a partnership between the federal government and industry. The government provides the legislative and regulatory structure for the regime and oversees industry’s preparedness and response activities. As the creator of the risk, industry bears the responsibility to respond to a spill and is always liable for spill response costs, including the operational costs of the regime.

Roles & Responsibilities

Canada’s spill response regime brings together components of industry, the provinces and federal agencies to protect Canada’s marine environment.

Transport Canada

Transport Canada is the lead federal agency responsible for the regime. It sets guidelines and regulatory structure as well as manages, monitors, reviews, enforces and implements standards and legislation. Transport Canada has a National Preparedness Plan that lays out the overall framework for the national capacity to combat marine oil pollution incidents in Canada. Transport Canada also oversees response organizations’ (RO) compliance with preparedness requirements through a triennial certification process.

Industry

Industry, including vessels and oil handling facilities, carries out its operational role through four government-certified ROs: WCMRC, ECRC, Point Tupper Marine Services and Atlantic Emergency Response Team. Each RO maintains plans, staff and equipment to respond to marine spills. To operate in Canada, industry is required to have an agreement with a RO to respond to a spill on the polluter’s behalf, and industry pays the RO an annual fee to maintain the level of preparedness required for spill response.

In addition, vessels that transit Canadian waters are required to have a shipboard oil pollution emergency plan, and oil handling facilities are required to have an oil pollution emergency plan as well as response equipment on-site. Should a spill occur, industry is required to manage the response and appoint an On-scene Commander.

Response Organizations

ROs are legislated to comply with Transport Canada-mandated operating standards as outlined in the Canada Shipping Act. This includes the capacity to respond to spills of up to 10,000 tonnes within prescribed timeframes and operating environments. ROs are required to have area-specific response plans and must demonstrate preparedness through a triennial certification process overseen by Transport Canada. Should a spill occur, the designated RO would be activated and would provide a response on behalf of the polluter.

Canadian Coast Guard

The Canadian Coast Guard (CCG) oversees industry’s operational role in the regime, ensures industry’s appropriate response to marine pollution incidents, and is responsible for national spill response management.

In the event of a spill, the closest regional CCG station would be called. If the polluter is willing and able to respond, CCG oversees the response as the Federal Incident Commander. If the polluter is unknown, unwilling or unable to respond appropriately, CCG takes charge of the response as On-scene Commander.

CCG also responds to minor spills and leads cross-border exercises with the United States.

Additional Federal Agencies

Additional pieces of legislation set out roles for other federal departments in the event of a marine spill:

- Environment and Climate Change Canada provides scientific, technical, environmental, and wildlife expertise during a spill, and manages the Science Table. The Science Table provides scientific advice to the On-scene Commander on appropriate methods and procedures to best cleanup the spill.

- Department of Fisheries and Oceans provides scientific expertise and information

Provincial Partners

Provincial partners in spill response vary depending on the region and scope of the response. Typically, a spill response will include the provincial Ministry of Environment, and representatives from other provincial organizations and authorities.

Planning Standards

Transport Canada sets out tiered response capabilities that ROs must meet to be certified to respond to spills in Canada’s waters. These planning standards specify the time within which an RO in a region must respond to a spill of a specified quantity. The standards also set out the number of metres of shoreline to be treated each day during a response operation and the number of days in which on-water recovery operations must be completed.

Certification & Exercises

Triennial Certification

To be certified as marine responders by Transport Canada, ROs must demonstrate their capacity to respond to spills under a variety of circumstances. This certification process is required every three years under the Canada Shipping Act. To meet the requirements, ROs hold tabletop and equipment-deployment exercises and oil spill response training courses within each certification period.

Annual certification requirements include:

- An executive summary of the RO’s oil spill response plan

- A description of the relationship to other spill response plans/management systems

- Complete details of the response organization

- Geographic Area of Response

- Emergency call-out procedure

- Personnel available to respond

- Equipment available to respond

- Health, Safety and Loss Control Program

- Site-specific Health and Safety Plan

- Response countermeasures

- Wildlife protection and rehabilitation

Exercises

Every Year

150 tonne equipment deployment

1,000 tonne tabletop scenario

Every Two Years

2,500 tonne equipment deployment

Every Three Years

10,000 tonne tabletop scenario

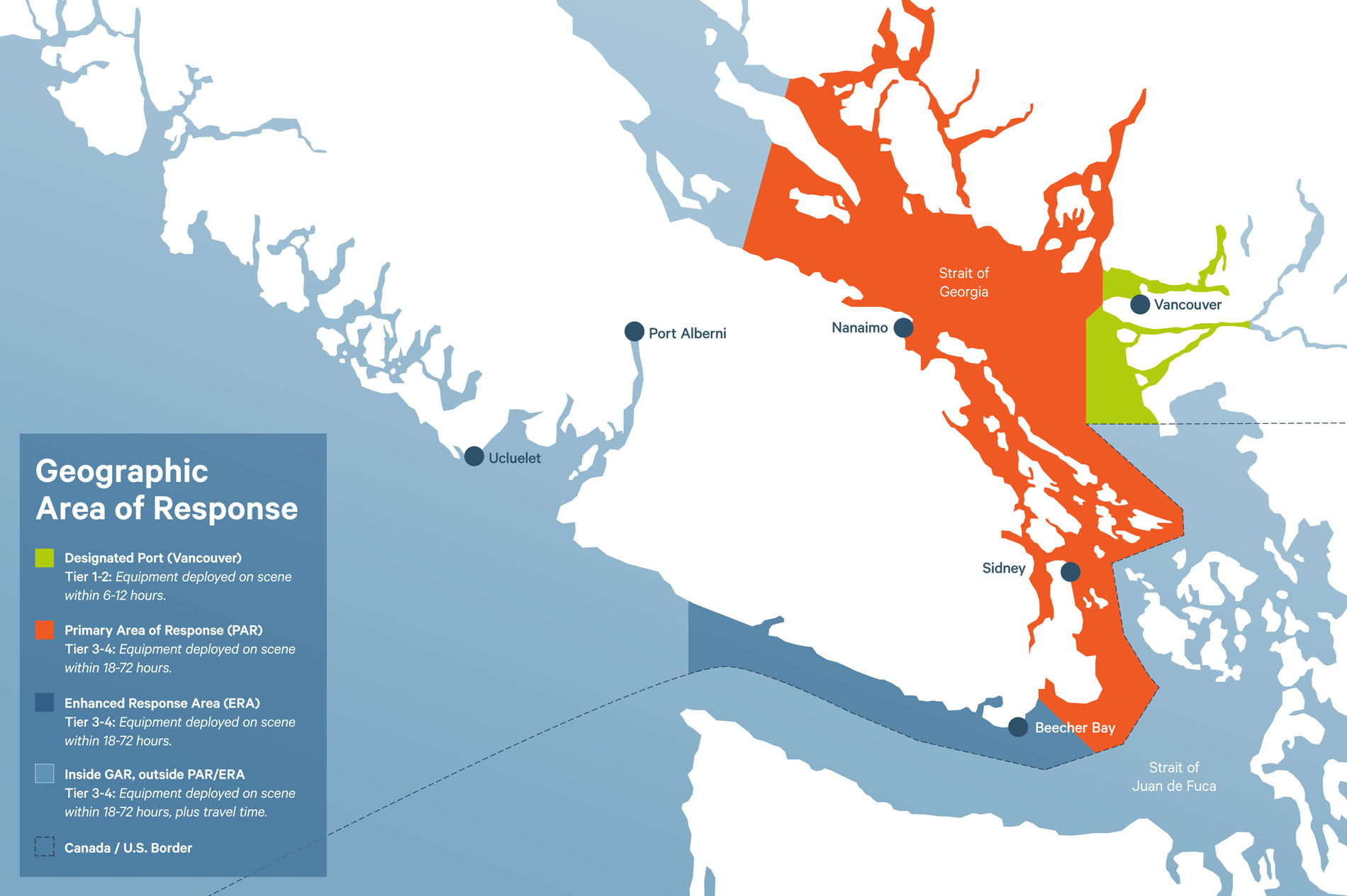

WCMRC’s Geographic Area of Response

WCMRC must demonstrate through certification exercises that it can adhere to response times set out by Transport Canada and specific to the areas detailed below.

Designated Port

The Port of Vancouver is impacted by traffic density and related ship convergence and must provide the necessary infrastructure to support the location of a certified response organization. The Port handles a minimum of 500,000 tonnes of oil annually. Transport Canada defines the Port of Vancouver as:

All the Canadian waters of Boundary Bay; the waters bounded by a line drawn from a point on shore originating at the Canada-United States border on Point Roberts due west along the international border to a point 123º 19.3’W, then north to a point 49º 14’N, 123º 19.3’W, then to a point 49º 15.5’N, 123º 17’W; the waters of Burrard Inlet east of a line drawn between Point Atkinson Light and Point Grey.

Response times within the Designated Port:

- Under 150 tonnes – Deployed on scene within 6 hours

- Under 1,000 tonnes – Deployed on scene within 12 hours

Primary Area of Response (PAR)

Because most large spills (>1,000 tonnes) occur outside port boundaries where vessels converge, the Canadian Coast Guard identified Primary Areas of Response as areas associated with Designated Ports that require a specific level of response capability and mobilization within designated times. The PAR for the Port of Vancouver is defined as:

All of the Canadian waters between the northern boundary of a line drawn from the point 49º 46.5’N, 124º 20.5’W on the mainland, through Texada Island, to the point 49º 22.5’N, 124º 32.4’W on the shore of Vancouver Island and the southern boundary consisting a line running along the 48º 25’N parallel from Victoria, eastward, to the Canada-United States border.

Response times within the PAR:

- Under 2,500 tonnes – Deployed on scene within 18 hours

- Over 2,500 tonnes – Deployed on scene within 72 hours

Enhanced Response Area (ERA)

Marine areas not covered under the above designation, but holding a higher risk of oil spills due to traffic convergence and volume of shipping, are identified as Enhanced Response Areas. The Strait of Juan de Fuca ERA comprises:

All the Canadian waters between the western boundary of a line drawn from Carmanah Point on Vancouver Island to Cape Flattery, Washington State, and the eastern boundary consisting of a line running along the 48º 25’N parallel from Victoria, eastward, to the Canada-United States border.

Response times within the ERA:

- Under 2,500 tonnes – Deployed on scene within 18 hours

- Over 2,500 tonnes – Deployed on scene within 72 hours

Liability & Compensation

Canada’s spill response regime is complemented by a liability and compensation framework set out in Part 6 of the Marine Liability Act. The Act implements several international conventions and establishes different liability and compensation regimes depending on the type of oil and type of ship involved in an incident. Generally, ship and cargo owners share the financial burden of providing compensation for ship-source pollution incidents.

There are several sources of compensation for marine oil spills:

Ship Owners’ Liability

In the case of a spill of crude oil, fuel oil (i.e. persistent oil) or bunker oil (which is used for ships’ engines) from tankers, the International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage and the International Convention on Civility Liability for Bunker Oil Pollution Damage make the ship owner liable. In both circumstances, the limit of liability depends on the size of the ship and is backed by compulsory insurance. If the amount of damages exceeds the ship owner’s liability, international and domestic funds provide additional compensation.

International Funds

Canada is a member of the International Oil Pollution Compensation Funds, which administers two international compensation funds for oil pollution damages caused by persistent oil. The first is the 1992 Fund and the second is the Supplementary Fund. Both hold levies collected from oil cargo companies.

Canadian Fund: The Ship Source Oil Pollution Fund (SOPF)

Canada created SOPF in the early 1970s from levies it collects from oil cargo companies. The SOPF pays compensation for oil spills in Canada from any type of oil and any type of ship.

International Cooperation

Canada and the U.S. have been working in close cooperation on preparedness and response for cross-boundary spills since the 1970s. A Canada-United States Joint Marine Pollution Contingency Plan was formalized in 2003, and joint exercises occur regularly to test the system. Canada also collaborates on spill response planning with other Arctic Council countries.

Regime Improvements

Regime review is conducted by Transport Canada to improve the national oil spill response regime. Recent initiatives include recommendations from the Tanker Safety Expert Panel and the Oceans Protection Plan.

The Tanker Safety Expert Panel

The Tanker Safety Expert Panel was established in 2013 to review Canada’s ship-source oil spill preparedness and response, and make recommendations to enhance the program. The panel has completed two phases of review and released two reports. The first focused on the overall state of Canada’s preparedness and response, and the second focused on preparedness and response for the Arctic and for hazardous and noxious substances nationally.

Oceans Protection Plan

The $3.5 billion federal Oceans Protection Plan was launched in 2016 and consists of over 50 initiatives to build national capacity and ensure maximum protection of Canada’s coastal resources. This program outlines measures on furthering collaboration with Indigenous and coastal communities, improving the efficiency, safety, and sustainability of Canada’s marine supply chains, and better management of marine traffic navigation off our coasts.

Regional Response Plans

Transport Canada is leading regional response planning initiatives based on a risk management framework. The regional response plans will be developed by regional task forces and will allow for regulatory flexibility for local differences and levels of risk. WCMRC and the Canadian Coast Guard have area-specific oil spill response plans that will be updated and integrated into the federal government’s initiative. These plans have been developed in collaboration with coastal First Nations, governments and communities.